It’s not surprising that we’re by no means the first folks to keep parrots as pets. These hook-billed birds have been fascinating people around the world for thousands of years with their intelligence levels, colorful feathers and powerful beaks.

Budgies are part of ancestral Aboriginal Dreaming stories, Alexander the Great has a parrot named after him because he introduced the species from Punjab to the West and The Sunday Times has an entire article dedicated to the appearance of parrots across art history.

I can go on, but I want to dedicate this article to some fun pieces of info I found while researching for the Indian ringneck parrot care guide. Namely, the fact that ringneck parrots from the genus Psittacula were prized pets in Ancient Rome and Greece, and we actually know quite a bit about what that was like.

The Romans, the Greeks & the birds

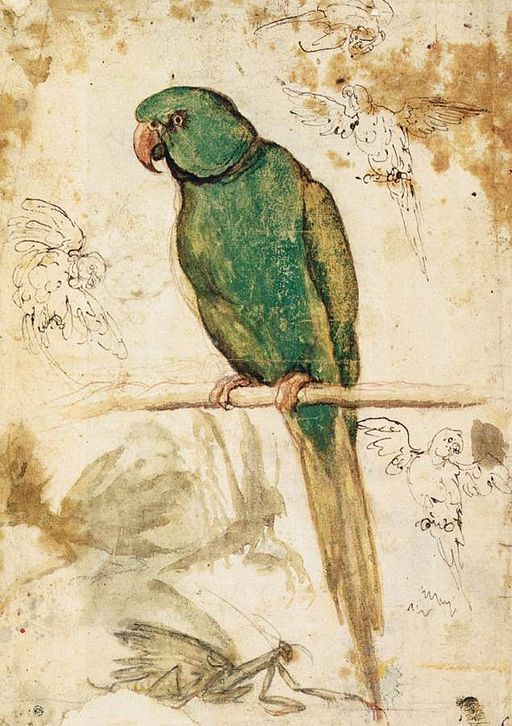

We know quite a bit about the daily lives of Ancient Romans and Greeks. It helps that these civilizations were pretty darn good about writing stuff down! Even the things they didn’t record in writing can sometimes be figured out pretty accurately through mosaics like the ones above, as well as a range of other artistic pieces.

It just so happens that these people really loved animals. In 1949, Lazenby describes in his “Greek and Roman Household Pets” how their strongly animal-based religions – many gods were depicted as various animals – probably contributed to them trying to domesticate all sorts of creatures. This included dogs, monkeys, snakes and, yes, parrots.

I couldn’t find much more about the Alexander the Great situation, other than that he apparently brought back a bunch of Psittacula parrots after his Indian campaign (around 325 BC). They must have made quite a splash!

According to the author of “Asia in the Making of Europe“, at the start of our calendar, the first century, trade relations with countries to the east (including India) had ramped up. A flood of exotic animals entered the Roman empire, making parrots a more common sight.

“From the first century B.C. onwards, Psittacula krameri and related species became very well known and, at least among the affluent classes, widely distributed pets in Rome and in the major centres of the Roman and Byzantine Empires (…)

There are dozens of ancient documents dealing with this and related species. It was depicted in wall paintings (e.g. at Pompeii) and in mosaics (e.g. at Rome and at Daphne near modern Antakya), and was mentioned by writers and poets.”

New records of Alexander’s Parrot, Psittacula krameri, from Egypt and the Levant countries by Kinzelbach, 1986

Writers and poets, you say? Many of these works are still available today, having conveniently been translated into every language under the sun. Let’s have a look at what these writers and poets have to say about those beautiful and strangely talkative birds from the East!

I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Writings & poems

Pliny the Elder talks about parrots

Pliny the Elder, who was a noted author and natural historian among many other things, wrote a little about his experiences with parrots. His Naturalis Historia (Natural History), considered by some to be the first encyclopedia, has received a lot of criticism in later years for what Brittanica calls “dubious accuracy”. Still, the 10th book, dedicated to ornithology, is a rich source of information about aviculture in the 1st century.

It seems Indian ringneck parrots were appreciated for much of the same reasons we keep them now: their intelligence, colors and superb speaking skills, among other things. Except for the bit where they’re given wine to drink!

“Above all, birds imitate the human voice, parrots indeed actually talking India sends us this bird; its name in the vernacular is siptaces” – noted to probably mean Psittacus, parrot – “its whole body is green, only varied by a red circlet at the neck. It greets its masters, and repeats words given to it, being particularly sportive over the wine.

Its head is as hard as its beak; and when it is being taught to speak it is beaten on the head with an iron rod – otherwise it does not feel blows. When it alights from flight it lands on its beak, and it leans on this and so reduces its weight for the weakness of its feet.”

Grieving a deceased pet

Pliny the Elder writes about the beautiful parrot with its red neck ring in a distanced, descriptive manner. Others weren’t quite so objective! In his book Amores (16 BC), poet Ovid laments the death of his mistress’ parrot in a pretty extensive elegy:

Parrot, the mimic, the winged one from India’s Orient, is dead – Go, birds, in a flock and follow him to the grave! Go, pious feathered ones, beat your breasts with your wings and mark your delicate cheeks with hard talons: tear out your shaggy plumage, instead of hair, in mourning: sound out your songs with long piping! (...) Your food was little, compared with your love of talking you could never free your beak much for eating. Nuts were his diet, and poppy-seed made him sleep, and he drove away thirst with simple draughts of water.

You can read the rest of that in Book II Elegy VI: The Death of Corinna’s Pet Parrot. And no, Ovid was actually not the only one who felt the need to remember a dead parrot through means of poetry!

Statius did something similar in his Silvae, published in the 90s of the first century. His 2.4, which is considered to likely have been modeled after Ovid’s work, discusses his friend Melior’s dead parrot:

Parrot, king of birds, your owner’s eloquent delight, Talented imitator, Parrot, of the human tongue, what Cut short your lisping with the suddenness of fate? Yesterday, sad bird, while we dined, you were about To die, though we watched you sampling the table’s Gifts with pleasure, wandering from couch to couch Past midnight. And you talked to us, spoke the words You’d learned.

Potty-mouthed birds

A while after Pliny, Ovid and Statius, around the 160s, Apuleius published his Florida (page 69). This author, too, talks about parrots. He describes them as Indian birds, bright green in color and with a ring around their neck. Discussing their ability to talk, he notes that young birds up to 2 years learn easily; after that, they become difficult to teach and forgetful.

Apuleius notes a significant disadvantage that comes with parrots’ ability to imitate human speech:

Teach a parrot to curse and it will curse continually, making night and day hideous with its imprecations. Cursing becomes its natural note and its ideal of melody. When it has repeated all its curses, it repeats the same strain again. Should you desire to rid yourself of its bad language, you must either cut out its tongue or send it back as soon as possible to its native woods.

Unsurprisingly, Apuleius wasn’t the only one to note parrots’ predisposition to becoming potty-mouths. Hundreds of years before, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle had already discussed the same thing. Like Pliny the Elder later does, he notes that the “Indian bird” is a fan of wine:

As a general rule all birds with crooked talons are short-necked, flat-tongued, and disposed to mimicry. The Indian bird, the parrot, which is said to have a man’s tongue, answers to this description; and, by the way, after drinking wine, the parrot becomes more saucy than ever.

THE HISTORY OF ANIMALS, 4th century BC

The parrot about as large as a hawk

If you think that Aristotle was the first writer in these regions to discuss parrots and their fascinating mimicry, you’re actually incorrect. It goes even further back than that!

The oldest text clearly mentioning the Indian bird that I could find was apparently Ctesias’ Indica, which was published roughly a century earlier, in the 5th century BC. I didn’t read it: it has actually been lost, but scholars have been able to more or less piece it together through other works quoting the Greek physician.

Ctesias wrote a lot of nonsense in his famed description of India – men with the heads of dogs, rivers of honey and people living for 200 years – but he was right about one thing. Even though he’d probably never seen one, as his work was based on stories he picked up, he wrote:

(…) of the parrot about as large as a hawk, which has a human tongue and voice, a dark red beak, a black, beard, and blue feathers up to the neck, which is red like cinnabar. It speaks Indian like a native, and if taught Greek, speaks Greek.

Photius’ Excerpt of Ctesias’ Indica

Know of any more texts about the ancient Greeks and Romans and their beloved Indian parrots? Feel free to leave a comment below!